Goal scorer Andres Iniesta of Spain celebrates as he lifts the World Cup with teammates after the 2010 FIFA World Cup South Africa Final match between Netherlands and Spain at Soccer City Stadium in Johannesburg. Jamie McDonald/Getty Images

John Doyle

The Globe and Mail

Published on Monday, July 12, 2010

That’s it then. Spain beat The Netherlands in a game that was persistently scrappy until extra-time. There were countess fouls. The main Dutch plan, facing Spanish artistry, was to kick at ankles, tug shirts, and manhandle opposing players. But Spain won – a victory of grace and technique over muscle and force. All good, really.

But that’s not the dominant story, is it? Certainly not in Canada and the United States. Soccer might have a new Word Cup champion, but some things never change.

If I am to take at face value the major themes in most of the North American press coverage of the World Cup, then two talking points emerge. First, there was some cheating going on in certain games. Second, South Africa will still be a country with problems of poverty and violence when the World Cup ends.

One can only nod in agreement, as when told that the Pope is indeed a Catholic.

On behalf of those who follow soccer week-in and week-out, year after year, even when there’s no World Cup looming, I am tempted to offer an apology. We are very, very sorry that the World Cup was not a month-long festival of Hallmark moments. We are sorry that FIFA is weirdly suspicious of video replay technology and doesn’t give a rodent’s posterior about the way things work in the NFL or the NHL. We’re sorry that Brazil doesn’t play samba soccer any more. We’re sorry that England went out early and you had to spend hours on Google researching players you had never heard of. We’re really sorry that Ghana failed to capitalize on that penalty kick, qualify for the Semi-Finals and give you an upbeat, feel-good story. Sorry about all that.

Me, I’ve been here, for a change, not at the tournament. That meant an education in local attitudes, especially media attitudes, toward soccer. Most mainstream media coverage of the World Cup has been a fascinating but often dismaying to read. (This newspaper excepted, of course.) Much of it, by reporters who usually cover North American pro sports, indicated a monumental misunderstanding of the game and sometimes a fundamental hostility to it. Certainly there was a failure to grasp the soccer mindset.

The first thing that certain parties need to grasp is that in the big ‘ol world outside North America, nobody actually cares if soccer makes inroads in popularity in Canada and the United States. The purpose of the World Cup is not to sell the sport to people normally devoted to the NFL, the NHL, NBA or Major League Baseball. Nobody who follows soccer is losing sleep about the game’s status here. Major League Soccer exists. The U.S. team did reasonably well and, no, the soccer world is not begging for your attention. Don’t need it, thanks.

Frankly, there is a fundamental disconnect between North American pro-sports coverage and the soccer world. Over the past month, I’ve read a vast amount of near-comical coverage of the World Cup by sports writers. Interestingly, the most incisive remarks about the game have come not from sports reporters, but from writers who can step back and see the larger context and that great disconnect.

In the New York Times, columnist David Brooks, who usually writes about economics and politics, was drawn into a debate about the difference between traditional American sports and soccer. He wrote this: “Football plays can be drawn up in a playbook and baseball lends itself to statistical analysis. But the rest of the world follows a sport that rewards resilience and neuroticism. Soccer is a sport perfectly designed to reinforce a tragic view of the universe, because basically it is a long series of frustrations leading up to near certain heartbreak.” Thanks, Mr. Brooks. At least somebody sees that soccer is not really a Hallmark moment kind of thing. You have grasped the mindset.

Part of the perverse pleasure of the World Cup is witnessing how soccer presents a challenge to those steeped in hockey, CFL or NFL football and such. Obviously, the World Cup and soccer itself is a gigantic and lucrative business machine. Simultaneously, it’s different from the North American sports model. Often in the past month I’ve been asked to explain “Why are so many people in the world so passionate about soccer?” I’ve tended to use one anecdote to explain.

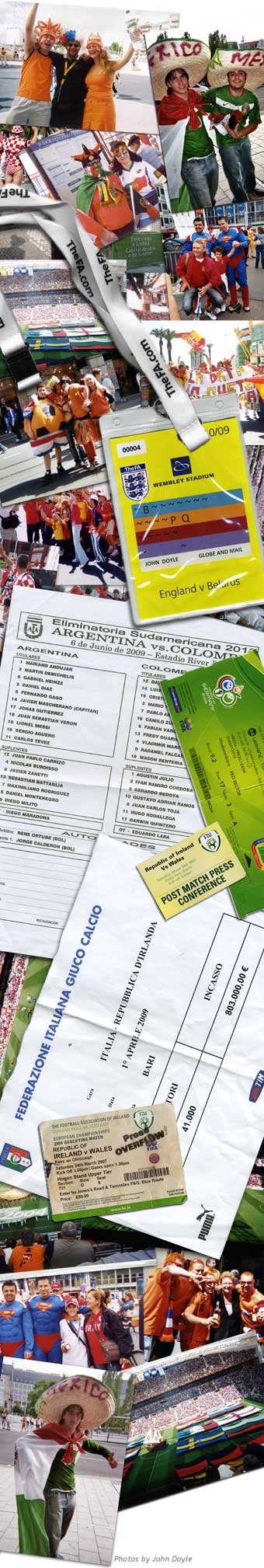

Last year I was in Buenos Aires to see Argentina play Colombia, a game at the stadium home of River Plate, one of the great club teams in Argentina. I’d noticed from the start that, in the stadium, certain areas were off-limits to media and fans. Corridors and rooms that looked vaguely different from what you find in most big sports stadiums. I asked my translator why there was a fuss about not entering those areas. He said, “Oh, that’s the school.” And I replied, “The school?” He explained, as one does to a visiting ignoramus, that the neighbourhood junior school was in the stadium. As the school in some other city might be part of a church or government building. River Plate, you see, is not a sports franchise in the way we understand an NFL or NHL team to be. Its soul and its stadium reside in a neighbourhood. Always has been there, always will be. Kids go to school in the stadium and nobody thinks that’s odd. Because River Plate is not going to pull out of the area, change its name and move to another city for tax reasons. That concept is utterly alien to the locals. The texture of the connection between the team and one part of Buenos Aires is just indescribably deep. In much of the world, soccer is like that – it’s not an entertainment enterprise. It is part of life itself. It’s not a TV show.

The World Cup also challenges the orthodoxy of North American sports reporting and sports-presentation. It’s TV rules that govern pro-sports in North America. Nice, understandable narratives of justice prevailing and lovable underdogs getting their reward. That kind of thing. In this context, even the smallest amount of diving or play-acting in soccer, and the lack of video-replay technology, is cause for livid indignation. Not because these things fundamentally diminish the sport, but because they are just different. And understood differently in the larger world. Different narratives for different folks.

At the start of he World Cup, I wrote an alleged defense-of-diving article for this paper. I also wrote a defense of FIFA’s reasons for ignoring replay technology. In each case I was merely being contrary, mainly because there has to be some sort of reply to all those calls and e-mails saying, “Soccer sucks.” I don’t care if you think it sucks. What I do care to enjoy, however, is undermining your vast and vapid assumptions about professional sports.

I mean, honestly – from the level of umbrage erupting over some play-acting and bad referee calls at a handful of World Cup games, you’d think there were no floppers or divers in the NBA (there are a lot) or the NHL. You’d think that video replay on TV represented the essence of moral purity. It doesn’t. You’d think it was normal situational ethics to ignore violence in hockey while expressing deep outrage at some excitable 23-year-old stopping a ball with his hand at the World Cup. You’d think the rest of the world was morally obliged to be like us.

In the end, of course, it comes down to the kids. That is, the response to seeing a fleeting moment of cheating go unpunished at a World Cup game invokes the ire of those who see everything as potentially undermining the innocence of children. Like patriotism, protecting-the-kids is the last refuge of the scoundrel. In North America there is a catatonically idiotic idea that, not only is it the purpose of sport is to teach kids life lessons, but that those lessons should be uplifting. This is, in essence, a belief in the superiority of fiction. In Hallmark moments.

Thing is, there can be useful truth as well as nice fiction in soccer. At one of the first World Cup games I attended, in Korea/Japan 2002, I was reminded of a core truth. Germany played Ireland in a key first-round game. The atmosphere was surreal, excited. I looked out at the tens of thousands of Irish supporters who had come all the way to Japan. Most of their banners declared allegiance to this or that pub, town or village. And in the middle was a tricolor flag with these words in giant letters: “It’s only a game.”

Tell that to the kids. It’s only a game and, sometimes, people are awful. They behave badly. Sometimes they win. So learn to lose, and fight another day. It builds character. It’s only a game.

Sorry if you didn’t enjoy the World Cup. Sorry if you think soccer sucks. But, in the big world beyond North America and its perceptions, nobody cares. If you know that Spain won by dint of dexterity and in winning represents the triumph of skill and finesse over ruthlessness, that’s all you need to know. That’s it then. See you for Euro 2012.