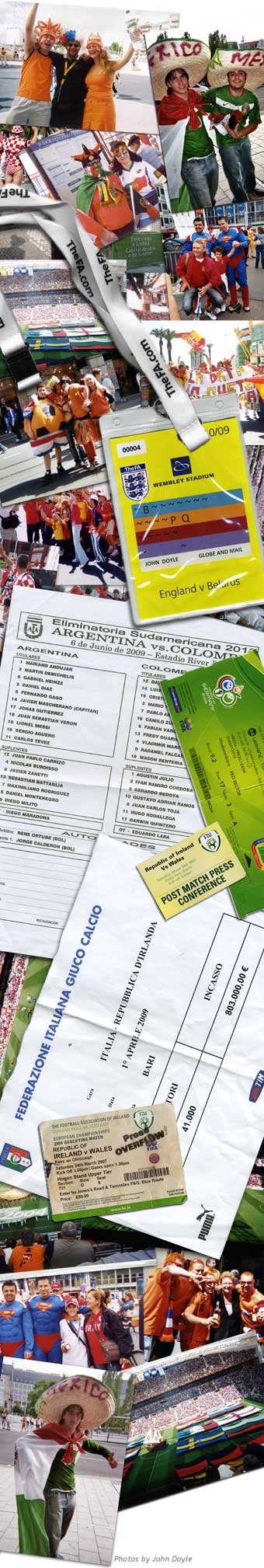

BUENOS AIRES — I came here to see a soccer game. Just for the weekend. A long trip for a short visit, but doable. Argentina was playing Colombia in World Cup qualifying on Saturday night, so it was going to be worth the time on planes and the money spent.

Like everyone coming here to see soccer — and soccer tourism is a growth business in beleaguered Argentina — I anticipated a fabulous atmosphere. Screaming, singing, chanting fans watched uneasily by police, just in case of real trouble. I saw the police, for sure, and the fans, all 45,000 at River Plate Stadium, but the cops were relaxed and the fans were the edgy ones — not enthusiastic rabble-rousers.

I learned a lot, but mainly this: In Argentina, nothing is what is seems. Everything in soccer is loaded with local meaning: the grass on the field, the number on the players’ shirts.

The game unfolded on a chilly evening but a true chill, the authentic sense of something cold and ominous, was in the air as much as the cold wind that had many of Argentina’s fans wrapping themselves in blankets. This was Diego Maradona’s must-win game in charge of the national team. He is worshiped here, but for his playing skills. In truth, he has yet to convince anyone that he can coach the national team.

The game unfolded on a chilly evening but a true chill, the authentic sense of something cold and ominous, was in the air as much as the cold wind that had many of Argentina’s fans wrapping themselves in blankets. This was Diego Maradona’s must-win game in charge of the national team. He is worshiped here, but for his playing skills. In truth, he has yet to convince anyone that he can coach the national team.

Argentina beat Colombia, 1-0. On paper, important points were gained in World Cup qualification. It was an improvement after Argentina’s 6-1 loss to Bolivia in April. In truth, it was an unconvincing win, marred by a raggedly chaotic display from Argentina in the first half. This became clear as soon as I sat down in the stadium.

Marcello Burello of the University of Buenos Aires had volunteered to be my guide and translator, and he pointed at the field. “It’s not as good as it looks,” he said. “The grass was painted green the other day. It’s in poor shape for an international game, so to make it look better they actually painted the grass.

“Maradona is supposed to be livid about it. But it’s not just about that. This is River Plate. He’s Boca Juniors. He can’t say anything positive about River Plate or this stadium.”

At the postgame press conference, in a bizarre, bravura one-man performance, Maradona ranted about the field.

“The field was impossible,” he said. “It was impossible to move the ball with ease. It was a field for horses, not football.”

Then he went on to declare that River Plate could not continue to be the home ground for Argentina.

“Unless there is a big change we will demand another stadium.”

Marcello whispered to me, “It’s about Boca and River Plate again.”

Late in the first half, with Argentina struggling to find a rhythm, one of three forwards, Sergio Aguero, was substituted.

“Strange time to make a change,” I said, thinking aloud. “It’s only five minutes to the break.”

My companion said: “Aguero is married to Maradona’s daughter. Probably picked because he’s the son-in-law. He looks useless, Maradona’s saving him from more embarrassment.”

Argentina found some discipline in the second half, but only a little. The loose 3-3-1-3 formation was abandoned. Maradona installed Javier Zanetti at left back, and something approaching coherence was achieved.

But it was still shocking to see the utter redundancy of Lionel Messi, possibly the most skillful forward in the world. He was easily hustled off the ball by Colombia and looked deeply frustrated as seemingly every ball sent to him by Juan Sebastian Veron, in midfield, was anticipated.

Messi, I noted, now wears the No. 10 shirt for Argentina. That was Maradona’s number, and it carries a burden.

In Argentina the player who wears the number is simply called “Ten” because he’s the playmaker, the magician who conjures chances from instinct.

“Who should be ‘Ten’ now?” I asked my translator.

“Riquelme,” he said, referring to Juan Román Riquelme. “But, you know, Riquelme fell out with Maradona a few months ago. They can’t stand each other.”

Even I, an outsider, knew Riquelme was a mercurial figure, given to public complaining. But he has been a startlingly inventive attacking midfielder for Villareal and Argentina. Surely differences could be put aside and the man persuaded to play for his country.

“No chance,” was the answer. “It got personal.”

There was relief, not celebration, when the game ended. The single goal by Daniel Alberto Díaz postponed panic about the inelegant, often chaotic, display by Argentina. But it was as temporary as the green sheen on the withering grass.

At Maradona’s press conference, he boasted of his halftime changes.

There were few direct questions for him, but much whispering in the room. The whispers increased when Maradona was asked why he had played Gabriel Heinze at left back in the first-half.

“I just decided!” Maradona shouted, and then chortled to himself.

The whispers, I was told, were about Maradona’s lack of reference to Carlos Bilardo, the former national coach he had appointed and welcomed as an adviser on his backroom team. Was Bilardo now out of the picture, as lacking in influence as Messi was on the field?

Later that night, in a Buenos Aires steakhouse, Marcello and I had dinner with Carlos Pachamé. He had been an assistant to Bilardo when Argentina won the World Cup in 1986. He was a legendary player for Estudiantes here and coached Argentina’s youth team. Few are as connected and wise about Argentina’s football success and secrets.

“Does Maradona listen to Bilardo?” I asked Carlos, as a delicate way of suggesting that Argentina had put in a shabby effort against Colombia.

A little unwilling to spill the beans about his personal chats with Bilardo, Pachamé said, “Maybe he asks but doesn’t listen. That is Maradona sometimes. He’s Maradona. Does he have to listen?”

I asked about Javier Pastore, a 19-year-old midfielder who is a scoring machine with Huracán in the Argentine league. Pastore has reportedly attracted bids from Manchester United, Milan and Lazio. Couldn’t he solve some of Maradona’s problems, liven up the national team, as Maradona once did himself as a teenager?

“First he has to marry Maradona’s other daughter,” Carlos said. And we all laughed.

To understand so much of soccer in Argentina requires insider knowledge. But Argentina’s situation under Maradona is no joke. It is shaky and uncertain. Of that I was certain after a weekend in Buenos Aires. It was worth the trip.