Xabi Alonso of Spain celebrates victory and a place in the final during the 2010 FIFA World Cup South Africa Semi Final match between Germany and Spain at Durban Stadium on July 7, 2010 in Durban, South Africa. 2010 Getty Images

John Doyle

The Globe and Mail

Published on Wednesday, July 7, 2010

Last week, this was South America’s World Cup. There was rabid speculation about a final featuring Brazil and Argentina. That hope evaporated in the quarter-finals. Now we know it’s Spain playing the Netherlands. What the two much-heralded teams South American lacked is what the finalists have – a tactical master plan anchored by specific use of midfield players.

Here’s why the South Americans crashed out – it’s a tale of tactical innocence and tactical cynicism.

Argentina. While Diego Maradona became a lovable figure at the tournament, thanks to his unbridled passion and visceral support of his players, as a manager he was revealed to be tactically naïve.

After an endlessly fraught qualifying campaign, it seemed that a chastened Maradona managed to forge a very male, very intense bond with the players in preparation for the World Cup. All enthusiasm, but no tactical plan. Crucially, Argentina lacked a principal holding midfielder, a playmaker to propel the team, to feed the ball to Lionel Messi and Carlos Tevez. An attacking midfielder, an engine of the team, is essential to take advantage of the natural skills of both. That’s what Holland has in Wesley Sneijder and Spain has in Xabi Alonso.

Argentina’s success at the World Cup in 2006 (it played the most attractive soccer and reached the quarter-finals, going out on penalties to Germany) was largely due to Juan Román Riquelme playing this role – fluent passing, setting the tempo and acting as a fulcrum of the team. Maradona’s achievement in getting Argentina through four games at the World Cup is notable but his greatest deficiency was his failure to persuade the mercurial and whimsical Riquelme to return to the national team. With some men, obviously, Maradona’s intensity and eccentricities just don’t work.

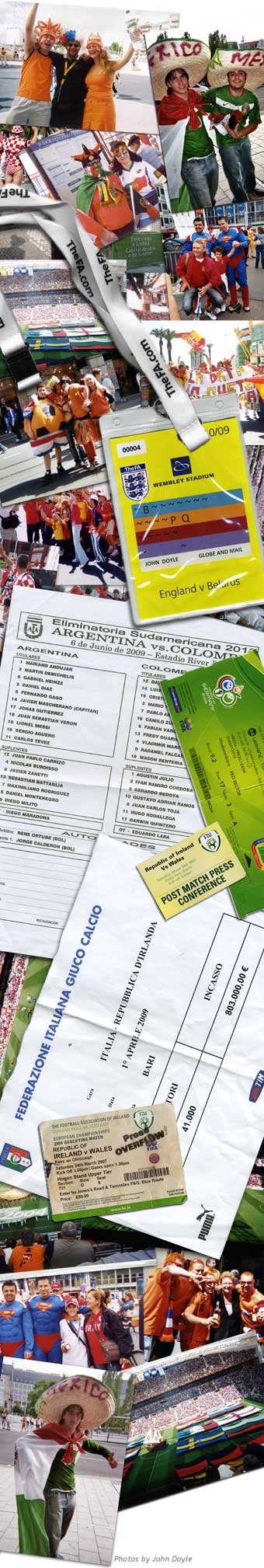

Mardona decided to play Juan Sebastian Veron in the midfield playmaker role, but Veron couldn’t do it. Javier Mascherano, who is essentially a more defensive midfielder, was tried in that role, but couldn’t do it. In fact, at times, Messi himself was playing the role – playing deep, and hence his lack of goals at this World Cup. This was a waste. Against Germany, in the quarter-final, the lack of any midfield plan was all too clear. Recently, I put this theory to a friend in Buenos Aires (my translator for a trip to see Argentina play Colombia in a qualifying game last year), who replied, “If you say ‘tactically naive’ you really fall short: We never had tactics at all. It was a question of trying to score spontaneously and defending miraculously, no matter what. Wonderful players, isolated on the field, “sweating the shirt” (it’s a favourite local expression), but with no team concept.”

That’s a damning indictment of Maradona, but accurate. Sentimentality may keep Maradona in his current role as manager, if he wants it. But sentiment is no substitute for a midfield or for tactical shrewdness.

Brazil. If a lack of tactics was Argentina’s downfall, then a far-too-rigid tactical blueprint was Brazil’s downfall. In fact, the intensity of disappointment is even worse in Brazil, and with good reason. In the last few days, manager Dunga seemed to quit and was simultaneously fired. He will not be missed. While much of the general criticism of Brazil has focused on the lack of flair, the disappearance of “Samba soccer” and Dunga’s failure to include such gifted players as Ronaldinho in his team, the reality is more mundane.

Unusually for Brazil, Dunga was firmly committed to a traditional 4-4-2 formation. Given the array of talents available, this wasn’t just a rejection of free-flowing soccer, it was absurdly limiting. Essentially it meant that Kaká formed a kind of forward line triangle with Robinho and Luís Fabiano, with Kaká’s role being largely defined by the forward movement of two attacking defenders – Maicon to the right and Michel Bastos on the left. If this rings a bell to some soccer geeks there’s a reason. The best description of Dunga’s formation was from a writer for The Guardian who described it as “ersatz Mourinho-esque.” This is all too true – Dunga seemed to learn exclusively from and copy the formidable tactical mind of Jose Mourinho, whose Inter Milan team won the European Champions League with a similar set of tactics and, indeed, with Maicon playing the exact same role he played for Brazil.

The Mourinho-esque style (it may change at Real Madrid now, who knows?) is to suffocate attacking teams with a rock-solid, four-man defence and two defending midfielders. Cut off passes and block opposing forwards from going anywhere. Scoring comes on the counter-attack, when space suddenly opens up. In the long marathon that is both Serie A and the Champions League this formation will work, grinding out victories here and there by small margins. But in the sprint that is the World Cup, an instant flexibility is required. For Brazil, there was no flexibility, no preparation for a Dutch side that relies not on a 4-4-2 formation but depends on the abilities of Arjen Robben and Dirk Kuyt to move endlessly on the wings and ceaselessly switch positions from left to right. As soon as Brazil went a goal down against Holland, all the limitations of Dunga’s plan became glaringly obvious. He was outmanoeuvred.

Dunga had no midfield maestro to conjure attacks. He had wingers and no middle. Ironically, the missing ingredient from the Mourinho-esque plan was playing for Holland. That’s Sneijder, who does do for Holland what he is often required to do for Inter Milan. In the end it didn’t matter that Ronaldinho – or Adriano – was missing from Brazil’s team. Neither would have fit in Dunga’s plan.

Dunga’s gone and, given Brazil’s depth of talent, the national team will re-invent itself soon enough. Argentina’s situation is different. Emotional attachment to Maradona means he might manage the team into next year’s Copa America, to be hosted by Argentina. His tactical sense had better change, or that will be another disappointment. Bluster can only take a team so far, especially if there’s still no midfield plan. As for Dunga, he could well turn up in Italy, copying Mourinho over and over again.

We’ll see by the end of Sunday’s game who ultimately emerges as the great stars of this World Cup. We already know it isn’t the expected names: Wayne Rooney, Cristiano Ronaldo, Kaka or Messi. In truth, the genuine stars will be midfielders – such names as Sneijder, Alonso or even the German Bastian Schweinsteiger, players who spend most of the game prowling the centre of the field, dictating play this way and that.